Hatshepsut (Early 18th Dynasty)

Page 1 of 1

Hatshepsut (Early 18th Dynasty)

Hatshepsut (Early 18th Dynasty)

In a documentary on female Pharaohs, I noticed an image that inspired me to look further into one of the Pharaohs. So far what I am reading has been interesting.

Has anyone heard of her before?

This is just a little overview I thought would be a good introduction to the Queen. It is from an article published in 2016 called “(De)queering Hatshepsut: Binary Bind in Archaeology of Egypt and Kingship Beyond the Corporeal” by Uroš Matić

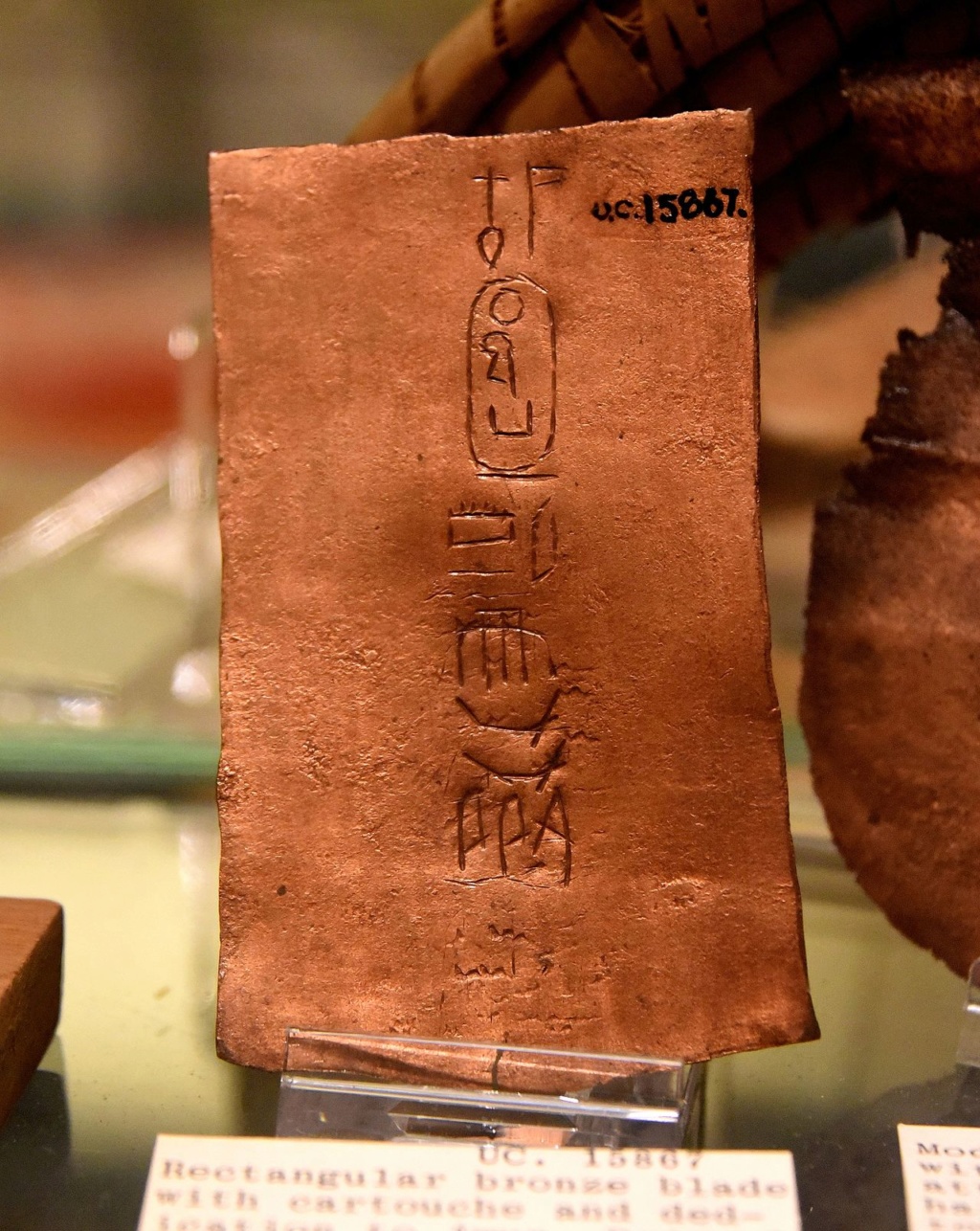

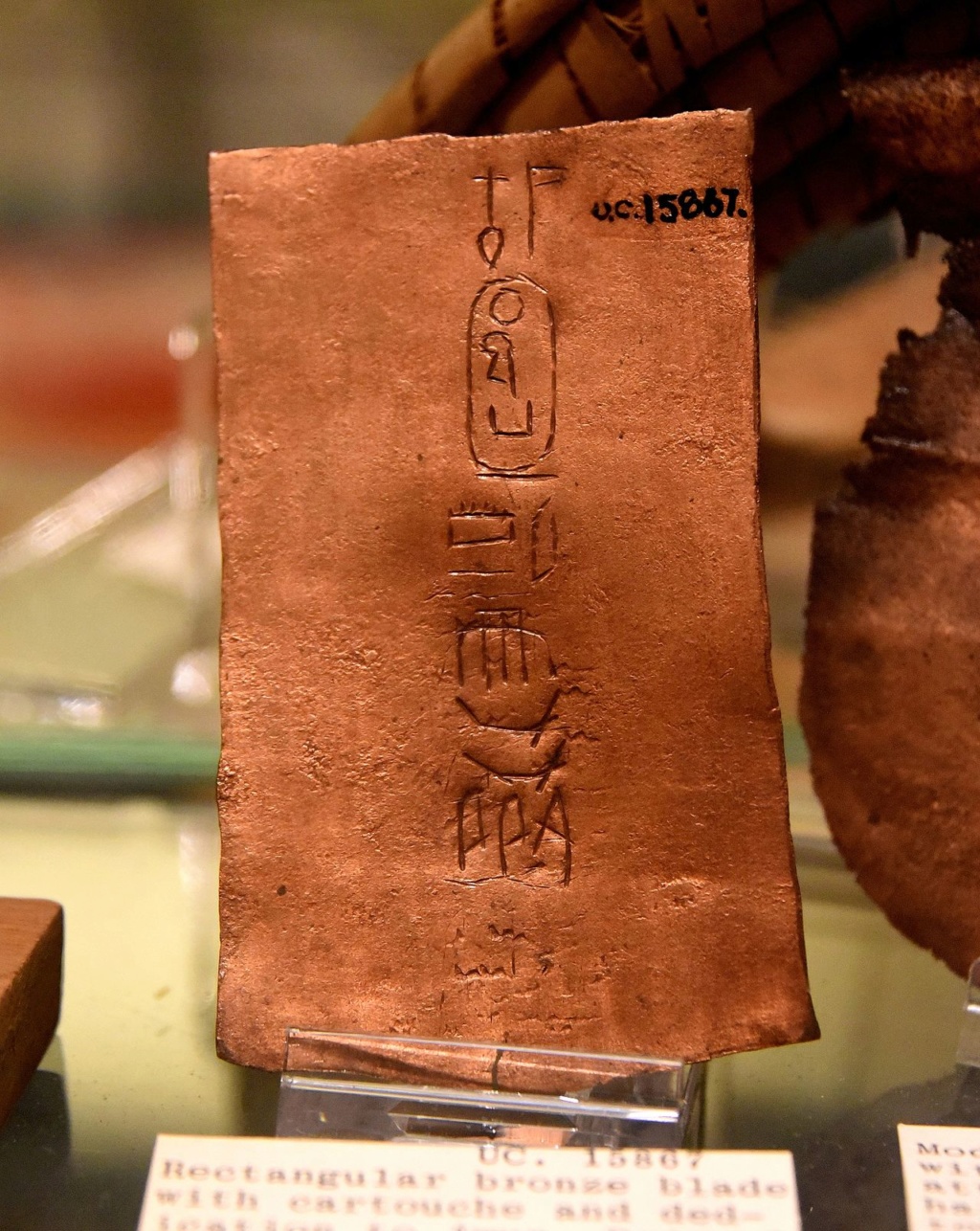

The images below are from a quick google search I first did to find out who she was.

Has anyone heard of her before?

This is just a little overview I thought would be a good introduction to the Queen. It is from an article published in 2016 called “(De)queering Hatshepsut: Binary Bind in Archaeology of Egypt and Kingship Beyond the Corporeal” by Uroš Matić

The images below are from a quick google search I first did to find out who she was.

UnseenUndine- Banned

- Number of posts : 77

Location : Springfield, Missouri

Registration date : 2017-09-14

Re: Hatshepsut (Early 18th Dynasty)

Re: Hatshepsut (Early 18th Dynasty)

In general chronological terms, the 18th dynasty (1550–1295 B.C.) dates to the Late Bronze Age, during which time Egypt had close contacts with the neighboring states of the eastern Mediterranean and the Near East. The history of the 18th dynasty starts with the defeat of the rival BHyksos^ kingdom in the north of Egypt (eastern Nile delta and Middle Egypt) under the first king of the 18th dynasty, Ahmose. He and his successors managed to extend the territory controlled by the 17th dynasty centered on Thebes (from which they originated), establish firm control, unify the land, and engage in military campaigns in Syria-Palestine and Nubia. It was during the 18th dynasty that Egypt reached the peak of its power and controlled its largest territory since the formation of its state. Hatshepsut organized expeditions to Punt, bringing frankincense and myrrh to Egypt, and commissioned many important building projects, including both the restoration of old structures—mostly temples—and the building of new ones.

The early 18th Dynasty is also known for its lack of male heirs produced by the royal couple. Thutmose I, third king of the 18th dynasty, had no surviving sons with his principal wife Ahmose; they had daughters named Hatshepsut and Nefrubity, the latter depicted with her parents in Deir el-Bahari. His son and heir Thutmose II was born by a secondary wife Mutnofret and probably became king after his father. Thutmose II married his half-sister Hatshepsut and reigned for only a few (roughly 3) years before his own death (Gabolde 1987: 67–68; Gabolde 2005: 149). Thutmose II and Hatshepsut also lacked a male heir, having instead a daughter named Neferure. The next king in line, Thutmose III, was born by a secondary wife of Thutmose II, named Isis (Большаков 2009: 142; Roth 2005: 11). Being that Thutmose III was very young at the time of his accession, it was necessary for a regent to take care of the actual governance. Indeed, although we do not know how young the new king was, he must have been very young, and Hatshepsut was as much as 20 to 25 years older. She is not mentioned in first orders issued by the king dated to the first 2 years of his reign, but the plans devised in these orders could not have been made by himself and were rather made in his name (Dorman 2006: 42–43). Hatshepsut thus governed the state from the very beginning. Before assuming the status of king, Hatshepsut first established herself in the temple imagery through association with the official king in depictions of divine cult, sometimes with Thutmose III and at other times instead of him. Within this royal function, she associates herself with her deceased husband Thutmose II (Laboury 2014: 67).

Sometime during the end of the seventh regnal year and before the turn to the eighth year of Thutmose III, Queen Hatshepsut was herself crowned king (Gabolde 2005: 151; Lansing and Hayes 1937: 20). According to Ann Macy Roth, there are three groups she took as models in her legitimization of rule: kings’ mothers, queen regents, and male kings (Roth 2005: 9). Of all the early 18th dynasty kings, it is likely that only Thutmose I came to the throne as an adult. Ahmose (first king of the 18th dynasty), Amenhotep I (second king of the 18th dynasty), and Thutmose II seem to have been quite young, perhaps even around 5 years old, at the times of their accessions. This means that women in the roles of kings’ mothers or queen regents ruled Egypt for almost half of the 70 years before Hatshepsut (Большаков 2009: 15; Roth 2005: 11). This is a crucial fact to be considered if one intends to argue that the New Kingdom Egyptians found women running the state to be problematic.

However, it is the model of the male kings which is of interest for the problems addressed in this paper. The institution of kingship in ancient Egypt was a male institution, with the male king being identified as a male falcon-headed god Horus during his life and as the male god Osiris during his death. The king was also the son of god Re, being a god himself only insofar as there was no intermediate term between human and god. An Egyptian king maintained order by defeating chaos and was himself a manifestation of god on earth (Baines 1995: 9). The institution of queenship was complementary to the one of kingship, and the one could not exist without the other. The position of the queen was also rooted in mythology and the divine world, as the queens played important ritual roles (Robins 1993: 42).

Hatshepsut is represented as a queen and god’s wife bearing her standard royal titulary at Semna temple under two regnal years of Thutmose III on the exterior face of the west wall (Caminos 1998: Pl. 42). Hatshepsut later changed the scene by inverting the direction of the goddess Satet to face her and modified her arms so that she receives from her tools of kingship, as Thutmose III does from the god Dedwen in Semna. Indeed, thus Hatshepsut connected herself to the White crown of Upper Egypt worn by Satet (Shackell-Smith 2012: 137). At Buhen temple in Nubia, she is depicted as a queen (royal widow) worshiping her deceased husband Thutmose II with Thutmose III. This image of her was later changed to make it male (Caminos 1974: Pls. 74, 82). She was also represented as a woman, before her representation was changed into that of a king, on the reliefs around the niche of a statue, on a back wall of the chapel of Senenmut at Gebel es-Silsilah. Here she is depicted in the embrace of Sobek on the left and Nechbet on the right, both using feminine gender in their direct speech to her (Kucharekm 2010: 150–151). The early focus on Thutmose II reflects her source of legitimacy as queen regent and god’s wife directing the state’s affairs in the name of Thutmose III.

Later at Karnak, she was depicted as directly undertaking the divine right, being depicted on a block from the Chapelle Rouge (the Red Chapel) in female dress, although with a regal plumed crown with ram’s horns and her cartouche with name Maatkare and title King of Upper and Lower Egypt (Chevrier 1934: Pl. IV). This points to the fact that adoption of the status of king did not entirely change her representations at the beginning but rather added to them royal regalia and a female royal name Maatkare. Thus, when she started her own sole rule she started it as a female pharaoh, depicted with her queenly gown and double-plumed headdress on top of her wig in performing the cult directly, a prerogative of kings. She is dressed as a woman and has female anatomy, but wears headdresses such as the ibes wig with a pair of tall feathers, which could be worn both by gods’ wives and kings, or a khat, a plain variant of nemes headcloath, which could be worn by male and female members of the royal family, as well as some goddesses (Laboury 2014: 72). In a scene from the fragmented barque chapel of Tura limestone from Karnak, she is transformed from a queen in a vulture headdress to a ruler with crook, flail, and nemes headcloath (Gabolde 2005: 109–113, Pl. XXXVI).

Hatshepsut used different resources to achieve what Virginia Laporta has termed Bontological change.^ These resources included ritual celebrations, the erection of monuments, and the adoption of the royal attributes of the King (Laporta 2012: 121). That is why we find Hatshepsut represented as a male king both in relief and statuary when she took on both the role and traditional names of the king (man), however in female gender (Robins 1999: 103). We find her with the red skin color that is mostly found with men in Egyptian iconography and with muscular and explicitly masculine morphology, but also with a new face that appears to be a synthesis of her previous facial representation with thutmoside face characteristics (with sesostride elements)— thus relating her through an ideological discourse with Thutmose I, her father, and Thutmose II, her half-brother and husband (Laboury 2013: 15–16). Her final transfor- mation of status meant fully adopting iconography of the king and his titles (names). It also meant abandoning expressions of legitimacy through her husband Thutmose II and the adoption of legitimacy through reference to Thutmose I her earthly father and Amun her divine father. She uses Wadjet-reneput as her nebty name, a name associated to patron goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, which is the feminine form of Wadj- reneput, an alternative Golden Horus name of Thutmose I found on his Karnak obelisk. Her first cartouche (an oval with a horizontal line enclosing the writing) name Maatkare can be associated to the one of Thutmose I, Aa-kheper-ka-re, and being that his Horus name was Meryt-maat, it is possible that this name is reflected in her choice of the name Maatkare (Robins 1999: 104–106). Her relation to Amun is expressed through the myth of her divine birth depicted and described in the temple of Deir el-Bahari.

Source: “(De)queering Hatshepsut: Binary Bind in Archaeology of Egypt and Kingship Beyond the Corporeal” by Uroš Matić

The early 18th Dynasty is also known for its lack of male heirs produced by the royal couple. Thutmose I, third king of the 18th dynasty, had no surviving sons with his principal wife Ahmose; they had daughters named Hatshepsut and Nefrubity, the latter depicted with her parents in Deir el-Bahari. His son and heir Thutmose II was born by a secondary wife Mutnofret and probably became king after his father. Thutmose II married his half-sister Hatshepsut and reigned for only a few (roughly 3) years before his own death (Gabolde 1987: 67–68; Gabolde 2005: 149). Thutmose II and Hatshepsut also lacked a male heir, having instead a daughter named Neferure. The next king in line, Thutmose III, was born by a secondary wife of Thutmose II, named Isis (Большаков 2009: 142; Roth 2005: 11). Being that Thutmose III was very young at the time of his accession, it was necessary for a regent to take care of the actual governance. Indeed, although we do not know how young the new king was, he must have been very young, and Hatshepsut was as much as 20 to 25 years older. She is not mentioned in first orders issued by the king dated to the first 2 years of his reign, but the plans devised in these orders could not have been made by himself and were rather made in his name (Dorman 2006: 42–43). Hatshepsut thus governed the state from the very beginning. Before assuming the status of king, Hatshepsut first established herself in the temple imagery through association with the official king in depictions of divine cult, sometimes with Thutmose III and at other times instead of him. Within this royal function, she associates herself with her deceased husband Thutmose II (Laboury 2014: 67).

Sometime during the end of the seventh regnal year and before the turn to the eighth year of Thutmose III, Queen Hatshepsut was herself crowned king (Gabolde 2005: 151; Lansing and Hayes 1937: 20). According to Ann Macy Roth, there are three groups she took as models in her legitimization of rule: kings’ mothers, queen regents, and male kings (Roth 2005: 9). Of all the early 18th dynasty kings, it is likely that only Thutmose I came to the throne as an adult. Ahmose (first king of the 18th dynasty), Amenhotep I (second king of the 18th dynasty), and Thutmose II seem to have been quite young, perhaps even around 5 years old, at the times of their accessions. This means that women in the roles of kings’ mothers or queen regents ruled Egypt for almost half of the 70 years before Hatshepsut (Большаков 2009: 15; Roth 2005: 11). This is a crucial fact to be considered if one intends to argue that the New Kingdom Egyptians found women running the state to be problematic.

However, it is the model of the male kings which is of interest for the problems addressed in this paper. The institution of kingship in ancient Egypt was a male institution, with the male king being identified as a male falcon-headed god Horus during his life and as the male god Osiris during his death. The king was also the son of god Re, being a god himself only insofar as there was no intermediate term between human and god. An Egyptian king maintained order by defeating chaos and was himself a manifestation of god on earth (Baines 1995: 9). The institution of queenship was complementary to the one of kingship, and the one could not exist without the other. The position of the queen was also rooted in mythology and the divine world, as the queens played important ritual roles (Robins 1993: 42).

Hatshepsut is represented as a queen and god’s wife bearing her standard royal titulary at Semna temple under two regnal years of Thutmose III on the exterior face of the west wall (Caminos 1998: Pl. 42). Hatshepsut later changed the scene by inverting the direction of the goddess Satet to face her and modified her arms so that she receives from her tools of kingship, as Thutmose III does from the god Dedwen in Semna. Indeed, thus Hatshepsut connected herself to the White crown of Upper Egypt worn by Satet (Shackell-Smith 2012: 137). At Buhen temple in Nubia, she is depicted as a queen (royal widow) worshiping her deceased husband Thutmose II with Thutmose III. This image of her was later changed to make it male (Caminos 1974: Pls. 74, 82). She was also represented as a woman, before her representation was changed into that of a king, on the reliefs around the niche of a statue, on a back wall of the chapel of Senenmut at Gebel es-Silsilah. Here she is depicted in the embrace of Sobek on the left and Nechbet on the right, both using feminine gender in their direct speech to her (Kucharekm 2010: 150–151). The early focus on Thutmose II reflects her source of legitimacy as queen regent and god’s wife directing the state’s affairs in the name of Thutmose III.

Later at Karnak, she was depicted as directly undertaking the divine right, being depicted on a block from the Chapelle Rouge (the Red Chapel) in female dress, although with a regal plumed crown with ram’s horns and her cartouche with name Maatkare and title King of Upper and Lower Egypt (Chevrier 1934: Pl. IV). This points to the fact that adoption of the status of king did not entirely change her representations at the beginning but rather added to them royal regalia and a female royal name Maatkare. Thus, when she started her own sole rule she started it as a female pharaoh, depicted with her queenly gown and double-plumed headdress on top of her wig in performing the cult directly, a prerogative of kings. She is dressed as a woman and has female anatomy, but wears headdresses such as the ibes wig with a pair of tall feathers, which could be worn both by gods’ wives and kings, or a khat, a plain variant of nemes headcloath, which could be worn by male and female members of the royal family, as well as some goddesses (Laboury 2014: 72). In a scene from the fragmented barque chapel of Tura limestone from Karnak, she is transformed from a queen in a vulture headdress to a ruler with crook, flail, and nemes headcloath (Gabolde 2005: 109–113, Pl. XXXVI).

Hatshepsut used different resources to achieve what Virginia Laporta has termed Bontological change.^ These resources included ritual celebrations, the erection of monuments, and the adoption of the royal attributes of the King (Laporta 2012: 121). That is why we find Hatshepsut represented as a male king both in relief and statuary when she took on both the role and traditional names of the king (man), however in female gender (Robins 1999: 103). We find her with the red skin color that is mostly found with men in Egyptian iconography and with muscular and explicitly masculine morphology, but also with a new face that appears to be a synthesis of her previous facial representation with thutmoside face characteristics (with sesostride elements)— thus relating her through an ideological discourse with Thutmose I, her father, and Thutmose II, her half-brother and husband (Laboury 2013: 15–16). Her final transfor- mation of status meant fully adopting iconography of the king and his titles (names). It also meant abandoning expressions of legitimacy through her husband Thutmose II and the adoption of legitimacy through reference to Thutmose I her earthly father and Amun her divine father. She uses Wadjet-reneput as her nebty name, a name associated to patron goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, which is the feminine form of Wadj- reneput, an alternative Golden Horus name of Thutmose I found on his Karnak obelisk. Her first cartouche (an oval with a horizontal line enclosing the writing) name Maatkare can be associated to the one of Thutmose I, Aa-kheper-ka-re, and being that his Horus name was Meryt-maat, it is possible that this name is reflected in her choice of the name Maatkare (Robins 1999: 104–106). Her relation to Amun is expressed through the myth of her divine birth depicted and described in the temple of Deir el-Bahari.

Source: “(De)queering Hatshepsut: Binary Bind in Archaeology of Egypt and Kingship Beyond the Corporeal” by Uroš Matić

UnseenUndine- Banned

- Number of posts : 77

Location : Springfield, Missouri

Registration date : 2017-09-14

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum